Opinion

OpinionAuthor’s Note: This article reflects the author’s personal views and analysis and is offered for general informational and academic discussion purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice, does not create an attorney–client relationship, and should not be relied upon as a substitute for legal counsel tailored to specific facts or jurisdictions. The author discloses an ownership interest in ChildSafe.dev and RoseShield™.

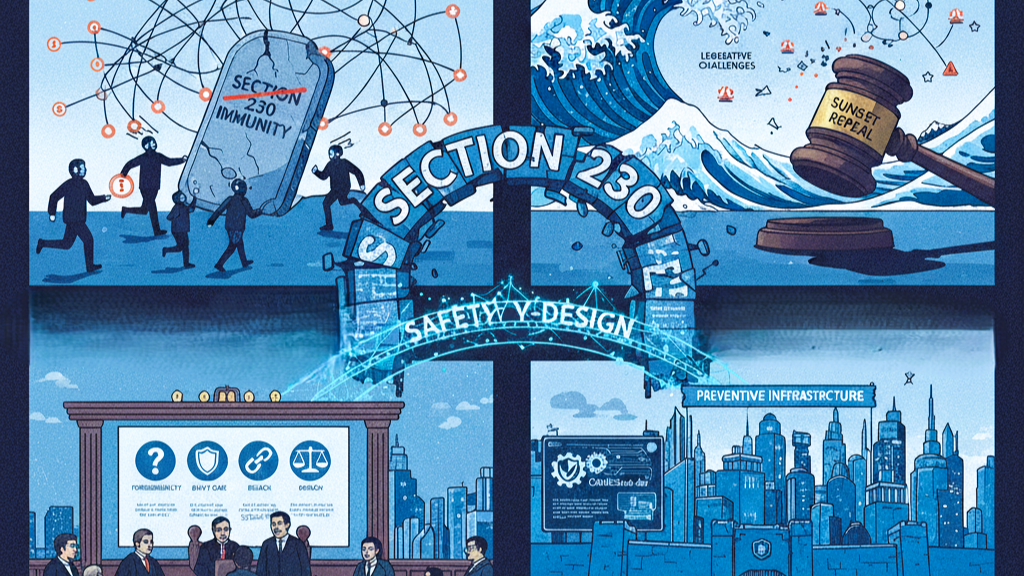

I left law school about the same time Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act came into existence. Since then, it has shaped the modern internet. Its central promise—that online platforms would not be treated as the publisher or speaker of user-generated content—enabled extraordinary growth, innovation, and scale. It also produced a predictable consequence: a business environment in which engagement and profit could be optimized with limited legal accountability for foreseeable harm.

With the introduction of legislation aimed at sunsetting or repealing Section 230 immunity, that equilibrium is changing. Whether repeal ultimately succeeds or not, the signal is unmistakable: the era of broad, unconditional platform immunity is drawing to a close. The implications of that shift are especially significant where children are concerned.

Section 230(c)(1) provides that platforms shall not be treated as the publisher of third-party content. Courts interpreted this provision expansively beginning with Zeran v. AOL (4th Cir. 1997), reasoning that liability would chill online speech and innovation. Over time, however, scholars have argued that judicial interpretation extended far beyond congressional intent. As Danielle Keats Citron and Benjamin Wittes explain in The Internet Will Not Break: Denying Bad Samaritans § 230 Immunity, courts have increasingly applied Section 230 to shield platforms that knowingly facilitate harmful conduct, rather than merely host neutral content (86 Fordham Law Review 401, 2017).

Section 230 never stated that:

What changed was not the statute itself, but how comprehensively immunity was applied to platform conduct.

Repealing or sunsetting Section 230 would not criminalize platforms. Section 230 is a civil immunity provision, not a criminal safe harbor. Its removal would instead reintroduce traditional tort and statutory analysis into the digital ecosystem. That analysis centers on four familiar elements:

Foreseeability, particularly in the context of child harm, is no longer seriously disputed. Congressional hearings and internal platform research disclosures have repeatedly demonstrated knowledge of risks associated with algorithmic amplification, sexual exploitation, and engagement-driven design choices (U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Consumer Protection, 2021). Platforms will, of course, continue to contest causation—arguing that user behavior, not platform design, caused the harm. That dispute will be central in future litigation. But once foreseeability is established, courts will increasingly ask a second, consequential question:

Were reasonable, technically feasible safeguards available—and were they deployed?

Sunsetting Section 230 shifts the inquiry from content to conduct.

Children occupy a distinct position in both U.S. and international law. They are:

This principle is reflected in COPPA, age-appropriate design codes, and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. In a post-230 environment, courts will scrutinize whether platforms knowingly placed minors into systems optimized for engagement without age-appropriate safeguards. The question will not be whether harm occurred—that record already exists—but whether reasonable preventive design choices were ignored.

Many platforms point to content moderation and reporting tools as evidence of responsibility. Legally, that argument is weakening. Tort law distinguishes between reactive mitigation and preventive design. As the Restatement (Third) of Torts explains, a failure to adopt a reasonable alternative design may constitute negligence when foreseeable risks could have been reduced or avoided (Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability § 2, Am. L. Inst. 1998). Post-hoc moderation does not eliminate foreseeable risk. Architecture does.

This is where safety-by-design infrastructure becomes legally salient. ChildSafe.dev and RoseShield™ are best understood not as policy tools, but as illustrative examples of a class of preventive, privacy-preserving safety architectures that demonstrate technical feasibility. (Disclosure: I am involved in this work.) Such systems matter in a post-230 world for several reasons:

These features are not ideological. They are legally relevant.

The Supreme Court’s recent decision in Gonzalez v. Google LLC, 598 U.S. ___ (2023), declined to directly narrow Section 230 but acknowledged unresolved questions around algorithmic recommendation and platform conduct. The Court’s restraint should not be mistaken for endorsement of the status quo. Rather, it underscores that the next phase of accountability will likely emerge through legislation and lower-court tort analysis, not sweeping judicial pronouncement.

Sunsetting Section 230 does not signal the end of the internet. It signals the end of the assumption that digital architecture exists outside the bounds of responsibility.

In the legal environment now taking shape, the decisive question will not be:

Did the platform intend harm?

It will be:

Did the platform take reasonable, available steps to prevent foreseeable harm—especially where children were concerned?

Safety-by-design infrastructure does not eliminate innovation. It aligns it with duty of care. And as immunity erodes, design choices will increasingly carry legal weight—whether platforms are prepared for that shift or not.

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization, client, or affiliated entity. This publication is provided for informational and academic discussion purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or a legal opinion. No attorney–client relationship is created by this publication. Any discussion of legal doctrine, pending legislation, or emerging liability frameworks is intended for scholarly and policy-oriented analysis only. Legal standards and interpretations vary by jurisdiction and are subject to change. The author maintains an ownership interest in ChildSafe.dev and RoseShield™, which are discussed as illustrative examples of safety-by-design infrastructure. Readers should consult qualified legal counsel regarding the application of these issues to specific circumstances.

© 2025 ChildSafe.dev · Carlo Peaas Inc. All rights reserved.

Built with privacy-first, PII-free child protection.