Opinion

OpinionThis article continues a series examining how responsibility for online safety is shifting from content moderation and post-harm enforcement toward system design. Earlier pieces explored the historical expansion of Section 230 immunity and the frequent misreading of Benjamin Franklin’s liberty-and-safety warning. This installment focuses on a quieter but consequential shift: why the long-standing tension between platform growth and child protection is becoming structurally outdated as technology, regulation, and tort principles converge.

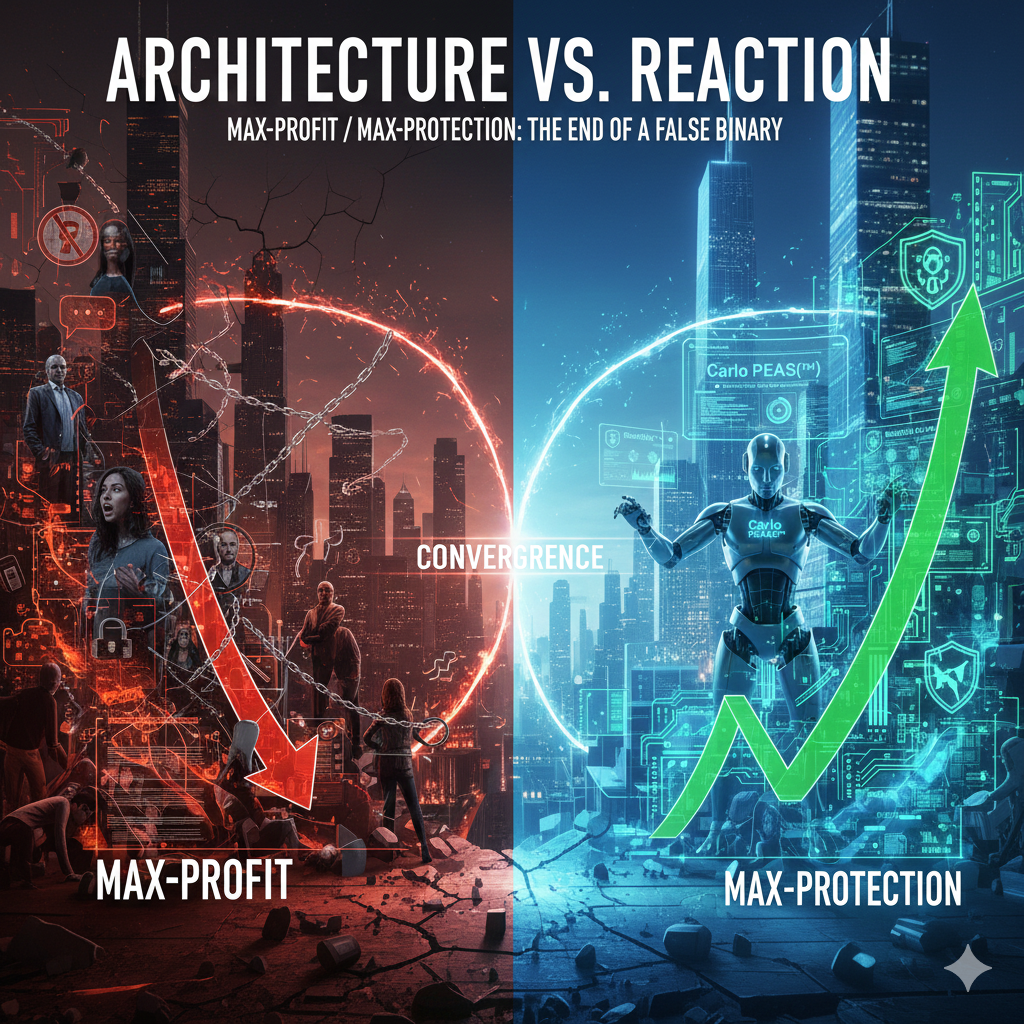

For more than 20 years, online safety—especially child safety—has been framed as a tradeoff. Platforms were told they had to choose:

In my opinion, that framing wasn’t dishonest, at the time.

Twenty years ago, preventing harm online was hard and expensive. Safety mostly meant:

Those approaches slowed growth and increased costs. At the same time, U.S. law gave platforms broad protection from liability for user-generated content (47 U.S.C. § 230; Zeran v. AOL, 129 F.3d 327 (4th Cir. 1997)). In that environment, the rational business move was simple:

Grow as fast as possible, deal with problems later.

That wasn’t negligence. It was a rational response to the technical and legal limits of the time (Kosseff, The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet, 2019).

What keeps getting overlooked is that we’re still arguing at the reaction layer, not the design layer. For years, safety lived downstream:

Harm happens → platforms react Moderation, takedowns, enforcement

That approach made sense when prevention wasn’t practical. But that world no longer exists.

In the 1800s, economist William Stanley Jevons observed something counterintuitive: when a process becomes more efficient, behavior changes. Efficiency doesn’t just reduce cost—it reshapes incentives (Jevons, The Coal Question, 1865). This is an analogy, not a perfect historical parallel—but it’s useful. I think the same thing is happening with online safety. Prevention's role changes as it becomes:

Safety no longer automatically slows growth. Instead, it can:

At that point, protection starts supporting profit instead of competing with it (Varian, Intermediate Microeconomics, 2019).

The legal system is beginning to reflect this shift—not loudly, but steadily. Regulators are increasingly asking whether platforms designed for foreseeable risk, especially where children are involved.

In U.S. courts, lawsuits are increasingly focused on product features, not user speech—particularly in cases involving alleged harm to minors (In re Social Media Adolescent Addiction Litigation, N.D. Cal., ongoing). Section 230 still exists, but courts are less willing to assume it covers every design choice (Gonzalez v. Google LLC, 598 U.S. 617 (2023)).

Children don’t experience online harm as single moments. Harm often builds over time—through repeated exposure, reinforcement, and dependency (Steinberg, Age of Opportunity, 2014; American Psychological Association, 2023). That matters because:

This reality fits prevention-by-design far better than after-the-fact enforcement.

We are no longer choosing between Max profit or max protection. We are choosing between:

The tension between platforms and safety advocates isn’t ending because one side won. It’s eroding because the underlying conditions have changed.

The real question isn’t whether platforms should protect children. It’s whether we’ll keep debating safety using frameworks that made sense 20 years ago—but no longer describe how technology, law, or risk actually work today. The architecture exists, the law is responding, the economics have changed. The only thing lagging seems to be the argument.

Disclosure: I am a lawyer and a co-founder of ChildSafe.dev, a company working on privacy-first, safety-by-design technologies relevant to the issues discussed here. The views expressed are my own. This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice or create an attorney-client relationship.

© 2025 ChildSafe.dev · Carlo Peaas Inc. All rights reserved.

Built with privacy-first, PII-free child protection.